Learn the science behind:

Making Confectionery Fondant: Controlling Sugar Crystallization

You may have eaten it without realizing. The ‘sister’ of the famous fondant used to decorate cakes: confectionery fondant. Made with just sugar, it’s a scientific feat. A delicate balance between crystallization & utter stickiness.

Confectionery fondant literally melts in the mouth. It’s a delicate balance of tiny sugar crystals, mixed into a sugar solution. The sugar crystals are as small as 20 microns! Nevertheless, you can make it at home! Controlling crystallization is key. Let’s have a closer look.

What is fondant?

Before diving into confectionery fondant specifically, let’s have a look at fondant in general. There are various types of fondant. Some are thick and can be kneaded and shaped into flowers. Others are thin and can be poured. But, at their core, all fondant types are about sugar.

If you’d zoom in on any type of fondant you’d find two key recurring components:

- A lot of very small sugar crystals, considerably smaller than those you’d find in your bag of sugar. These tiny sugar crystals ensure fondant has a smooth texture.

- A very concentrated sugar solution surrounds the sugar crystals. It’s what ensures it doesn’t crumble or turn powdery.

Fondants might contain some other ingredients such as fats from butter or oils, or proteins from milk or gelatin. But it’s the sugar that’s the main actor here.

A scientist would describe a fondant as:

“A partially crystalline (…) confectionery ingredient with numerous small sugar crystals held together by a saturated sugar syrup.“

R. W. Hartel, J.H. von Elbe, R. Hofberger, Confectionery Science & Technology, Springer, 2018, p.245

What is confectionery fondant?

Confectionery fondant is one of the simplest types of fondant. It can be made with just sugar(s) and water. The final product is a firm, smooth product. It can be shaped into a ball, but if left for a few days will flatten out slightly again. It’s often not strong enough to hold onto its shape. It is distantly related to maple cream. This ‘fondant’ isn’t as firm and is made from maple syrup.

Note, the definition of confectionery fondant tends to vary widely. We found confectionery fondant to be the most descriptive and consistently used for the fondant type described above. However, you might well know it under a different name.

Wondering what to use confectionery fondant for? Well, it’s used to make a range of other crystalline candies, e.g. borstplaat, a typical Dutch sweet and can also be used to help along fudge.

Rolling fondant – a cake decorator

Probably the most well-known type of fondant is rolling (or rolled) fondant. This is a very firm and sturdy type of fondant. You can easily roll it into thick sheets. Drape these sheets on top of a cake and you have a beautiful canvas for decorating.

Just like any other fondant, rolling fondant contains a lot of small sugar particles as well as dissolved sugar. However, aside from that, it often also contains some other ingredients. Gelatin helps make the fondant stretchy. Fat from butter or cream makes it easier to handle. Glycerin helps to keep it moist.

Pouring fondant – fluid and pourable

Lastly, another very commonly mentioned type of fondant is pouring fondant. As the name says, this fondant can be poured. It’s a lot more liquid than both rolling and confectionery fondant. It is often used to decorate baked goods, and give them a nice shine.

Some types of pouring fondant are almost identical to a basic confectionery fondant. The main difference is the amount of water, making it more liquid. However, some pouring fondants also contain some additional fats to improve consistency and smoothness.

What happens when making confectionery fondant?

Recall that fondant consists of two key phases: small sugar crystals + a concentrated sugar solution Confectionery fondant doesn’t contain any other ingredients. It’s made of just these two phases. So let’s have a closer look at how you can make these two phases.

Making confectionery fondant consists of two crucial steps (watch the video above to see what happens):

- Boil sugars in water until a set temperature

- Cream the resulting sugar solution

Step 1: Concentrating the sugar solution

Fondant contains tiny sugar crystals. However, regular white sugar is made up of large sugar crystals. To make small crystals, we first need to get rid of these large crystals. You do that by dissolving the sugar in water.

A sugar crystal is made up of sugar molecules. These have organized themselves tightly to create a crystal. Sugar molecules are good at doing so. You use this property when making rock sugar for instance. But, if enough water is present, the crystal will break down. All the individual sugar molecules will let go of one another. They’ll each swim individually in the water.

Once all sugar crystals are gone, it’s time to bring them back again, but in a smaller size. To do this, you have to get rid of some of the water again.

Sugar crystals only crystallize when they can no longer roam freely in the water. This happens once the sugar solution is supersaturated. A supersaturated solution contains more dissolved sugar than is energetically stable. At the slightest push, e.g. stirring, sugar molecules will grow crystals!

Making a supersatured sugar solution

You can make such a solution by evaporating water from a sugar solution, it is key to many candy types. You do so by boiling a sugar solution. During cooking, the sugar won’t evaporate, it’s just the water that disappears. As a result, the concentration of sugar increases.

Did you know that the boiling point of a sugar solution depends on the concentration of sugar? The higher the sugar concentration, the higher its boiling point! Want to learn more about the scientific principles behind this phenomenon?

Step 2: Crystallizing sugar by mixing

Once you’ve evaporated enough water, it is time to make crystals. To understand what happens, it’s important to understand the effect of temperature on sugar solubility.

The hotter a sugar solution, the more sugar can be dissolved. However, once you cool down the sugar solution, there is less ‘space’ for sugar to be dissolved. As a result, by cooling down the sugar solution that has been boiling away for some time, you’re automatically causing it to become supersaturated.

If you just leave a sugar solution to cool down now, it will start to crystallize. It might take a while, but it will turn hard. The crystals will form randomly. Likely, only a few, very large crystals will form. This is not what you want in confectionery fondant.

Creating many small crystals

Luckily, there’s a way to prevent the formation of these large crystals: continuously mix the sugar solution while it’s cooling down. Mixing causes larger sugar crystals to break into smaller ones. Also, mixing causes more sugar molecules to find each other and start forming crystals. As a result, you’ll end up with a lot of very small crystals.

This is exactly what you want in a confectionery fondant!

In the video above you can see this transformation happening as we’re cooling down and simultaneously mixing the fondant mix!

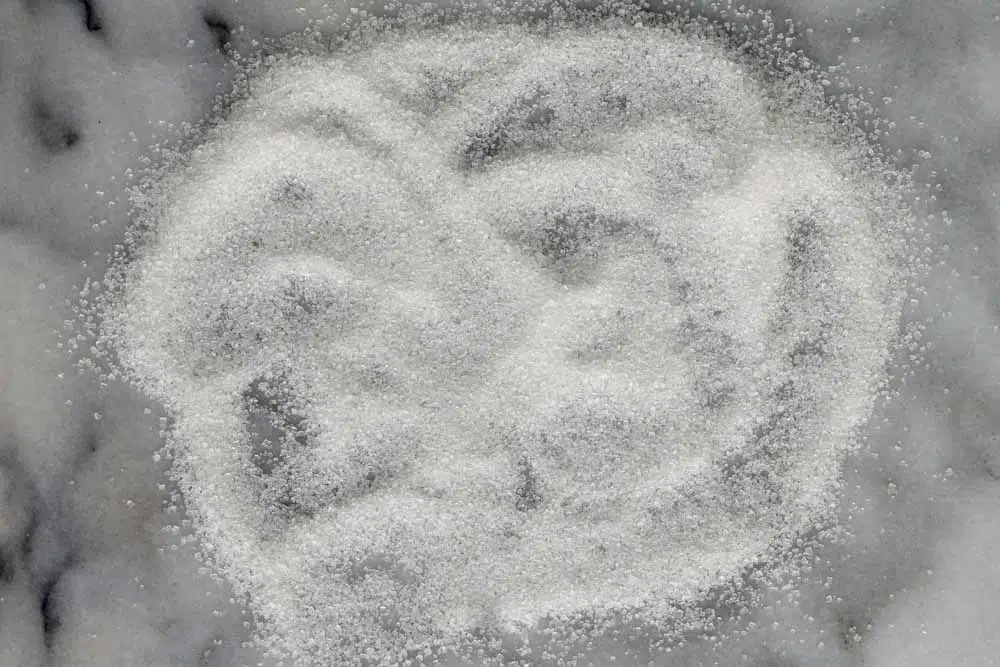

Left: this fondant has been mixed well and continuously while cooling down. Tiny crystals have been formed, making a very smooth fondant that can be kneaded by hand.

Right: this fondant has not been stirred well. It is very brittle and rough. It cannot be kneaded by hand.

Final product: not just crystals

Even though you’ve crystallized a lot of sugar, the final product doesn’t just consist of these tiny sugar crystals. If that had been the case you’d have made a powder.

Instead, you have sugar crystals that are dispersed into a saturated sugar solution. What happened here?

Remember that only so much sugar can dissolve in water? Well, sugar will continue to crystallize from the water, until this concentration has been reached. Once the maximum concentration has been reached and there is no longer excess sugar in the water, the remaining sugar will remain dissolved.

When making confectionery fondant you don’t evaporate all water (like you’d do for caramelizing sugar). Instead, you leave in enough water so some of the sugar can remain dissolved. This is important. This liquid sugar solution ensures the confectionery fondant is flexible and moldable.

The presence and balance of sugar crystals and sugar solution is governed by the temperature to which you boil the sugar solution. It involves some complex scientific phenomena that are often explained using phase or state diagrams.

Role of ingredients in fondant

You can make a confectionery fondant with just sugar and water. However, in most cases, it’s easier to also use either some corn syrup or some sort of acid. Together they help steer crystallization in the right direction. So let’s have a look at each.

White sugar – the star player

Making confectionery fondant can’t be done without regular white sugar. This sugar, which is made up of sucrose molecules, is what will form the tiny sugar crystals.

Water – the adjutant

To make confectionery fondant, water serves as a crucial helper. It ensures you can dissolve all the large sugar crystals at the start of the process. In the final product, water is essential to create a sufficiently soft and kneadable fondant.

Corn syrup – prevents overenthusiastic sugars

Corn syrup, also referred to as glucose syrup, is often added to help control sugar crystallization. Sucrose molecules have a strong tendency to crystallize when they can. Some sugar crystals might already start to crystallize on the sides of a cooking pot. Or, they might crystallize too quickly. Corn syrup prevents this from happening.

Corn syrup is made by breaking down large starch molecules into smaller molecules. Some of these are sugars, providing sweetness. However, some of these very large molecules will remain in the syrup. These large molecules serve as a barrier for sucrose molecules to meet one another. As a result, it prevents crystallization from happening prematurely.

Corn syrup serves a very similar role when making things like caramels or caramel sauce!

Acids – breaks down some sugar

It’s the sucrose molecule that crystallizes when making fondant. One sucrose molecule is again made up of two molecules: glucose and fructose. By breaking down sucrose into fructose and glucose, you can prevent crystallization.

You can accelerate the breakdown of sugar, by adding some acid to the boiling water. It’s why some recipes may call for a little vinegar, lemon juice, or juice of tartar.

When sucrose is fully broken down, you end up with invert sugar.

Troubleshooting confectionery fondant

Followed all the right instructions and used all the described ingredients, but still not getting the result you’re looking for? Let’s do some troubleshooting! If you’re ready to give this less-well-known fondant a try? Scroll down to find a recipe to get you started!

It seems you’ve created unfavorable conditions for crystallization to happen. There are a few possible reasons:

1. Too much corn/glucose syrup: corn syrup can slow down crystallization, however, use too much and it can prevent crystallization from occurring at all! Lower the corn syrup content if this might have happened.

2. Too much acid: acid breaks down sugar molecules. A few broken sugar molecules are good, they help make a soft fondant. Too many, not so great. Reduce the amount of acid.

3. Cooked too slowly for too long: this is most likely to happen when you’ve also added extra acids. Acids break down sugars over time. If you cook your sugar solution very slowly, for a long period of time, too many sugars break down. Cook smaller batches to reduce cooking time, or use a more effective heater to cook more quickly.

To prevent premature sugar crystallization, add an ingredient that slows it down. You could add some corn syrup, or a little acid.

If you don’t want to add any other ingredients, be very careful when boiling the sugar solution. The tiniest sugar crystal on the side of a vessel may induce crystallization.

Add a little extra water. The extra water will cause a few of the sugar crystals to redissolve. This softens the fondant as a whole. Do make sure you knead the fondant well to mix it all through homogeneously.

This can also happen if you do not store the confectionery fondant air-tight. Over time moisture will want to escape from the fondant, so store in an air-tight container.

Confectionery Fondant

Confectionery fondant can be used as-is. It is also often used to make a wide variety of other sugar candies. The tiny sugar crystals in the fondant help in making fine crystals in products such as fudge or borstplaat.

It is easiest to make fondant using a stand mixer. It's a very hands-off method.

Ingredients

- 300g sugar (regular white sugar, e.g. granulated or caster sugar)

- 50g glucose syrup*

- 60ml water

Instructions

- Add the ingredients to a pot and bring to a boil.

- Continue to cook to 118°C (245°F). There should be no need to stir, just leave it be as much as possible.

- Turn off the heat and leave to cool down for a few minutes.

- Pour the, still hot, sugar syrup (it should have thickened slightly) into the bowl of a stand mixer.

- Use the paddle attachment and mix the sugar solution at the lowest speed.

- Initially, not much will happen. However, as the sugar solution cools down you will see it start to turn thicker and whiter in color. Continue mixing until the mix has turned white and has cooled down enough to knead by hand.

- Take the mix from the mixer. It should have formed a white smooth paste. By hand, lightly knead the paste into a smooth ball. This helps any remaining pieces to mix in and crystallize.

- Store in an air-tight container. It can be stored for weeks this way, the high sugar content is a good protective barrier against spoilage!

Notes

*Glucose syrup may also be referred to as corn syrup, depending on where you live.

References

Veena Azmanov, How to make rolled fondant icing, Nov-15, 2020, link

Chocolate Candy Mall, Fondant, link

Eddy van Damme, Fondant, Feb-15, 2010, link

The French Pastry Chef, Fondant, link

R. W. Hartel, J.H. von Elbe, R. Hofberger, Confectionery Science & Technology, Springer, 2018, chapter 9, link

Erin Jeanne McDowell, Think You Hate Fondant? Think Again., Nov-5, 2021, link

What's your challenge?

Struggling with your food product or production process? Not sure where to start and what to do? Or are you struggling to find and maintain the right expertise and knowledge in your food business?

That's where I might be able to help. Fill out a quick form to request a 30 minute discovery call so we can discuss your challenges. By the end, you'll know if, and how I might be able to help.

Thank you for your very informative article. I am interested in making fondant candies that involves reheating prepared fondant, and pouring the heated fondant into moulds. The candies harden into very firm pieces. My question is, do you have any information on this technique, specifically: to what temperature do I reheat the fondant to prior to pouring into the moulds, and, is this done on direct heat or by using the double boiler method?

I appreciate any direction you can give me.

Heather P.

Hi Heather,

I’m not familiar with making fondant candies that only require reheating of fondant. I’m more familiar with processes in which you also add some other ingredients. But, I’ve tried to list a few thoughts below, hope those give you enough direction to continue your endeavors!

Hope that helps, please don’t hesitate to ask further questions if it does not :-).

Thank you for your reply. I am trying to re-create a Scottish candy from my youth that was sold in almost every store – sugar mice. It dates back to Victorian times. The candy was quite hard and slightly granular, and tasted like unflavoured sugar. It was in the shape and size of an actual mouse (No chocolate coating). You needed very strong teeth to eat it (It may explain all my dental fillings). After reading your response, I think the reheated candy will have to be brought to a higher temperature (as opposed to just melting the fondant) in order to have the granulation occur. I have been looking for this technique for years. There is a video on Youtube called “How to Make Sugar Mice”, posted by Michael Dickson. It is 2:12 long, and shows the sugar mice being produced in a factory in Wales. Unfortunately, they don’t provide any actual details on temperatures and techniques, other than to say that the cooked fondant is made initially, then is reheated prior to filling the moulds. This will be my Christmas project…trying to narrow down the temperatures and control the extent of the granulation. I will let you know when I am successful. Thanks again!

Hi Heather,

I’ve done a little more digging and had a look at the video you suggested. It does seem to say that you should only warm up the fondant, just until the boiling point. Other recipes that I found online also all seem to use just regular fondant. What I’m thinking is that these mice get their hardness because they’re left to dry out. So, they’d be a little soft after making, but will harden over time. After shaping, they are left open to the air. That way, moisture evaporates and continues to harden them out. Could that be it?

As you’re probably already aware, there are a lot of different types of fondants out there. So if you’re buying fondant, make sure you don’t have the one that’s used to cover cakes for instance, that one will never harden out enough.

If you’re making your own fondant, I’ve come across some recipes using egg whites (just like you’d do in a royal icing). Egg whites can really help harden a fondant, so that might make a difference. I have a suspicion that most of the online sugar mice recipes won’t make an exact replicate of ‘your’ sugar mice, since the homemade versions often need to be adjusted a little. But maybe this one from the bbc, if you didn’t already find it yourself, can provide some further guidance?

Hello, and Happy Holidays!

Thank you for your ongoing assistance with my fondant studies. I am afraid the egg white fondant is a whole different animal and not what I am looking for. Are you familiar with Canadian Maple Leaf Sugar Candy? It is typically made in the shape of maple leaves. It is very crystalline and quite firm to the tooth. The maple syrup is cooked to 240 F, cooled to about 170F, stirred briefly, then poured into maple leaf moulds. The fondant candy I am trying to recreate is similar to this granular texture, but of an even firmer mass that can only be snapped in half with quite a lot of force. Any thoughts on how to forgo the fondant aspect, and work with a simple sugar syrup instead?

Hi Heather,

I’m not very familiar with that candy, though I think I’ve come across it before. It sounds a little bit like fudge making this one. The stirring at 170F is probably done to initiate crystallization of the sugar, ensuring the candy crystallizes properly.

The interesting thing about maple syrup is that it’s not pure sucrose (regular sugar), it’s a mix of sugars that probably helps to create this nice texture. If you’d want to give it a go iwth other sugar syrups you shouldn’t try the ‘regular’ corn syrups etc., instead, maybe opt for an agave syrup? It won’t have that maple flavor (that you wouldn’t want) and might do something similar, though I’m afraid you’d have to experiment a little with temperatures since they’ll likely be slightly different.

It sure is a challenge you’ve set yourself Heather! I hope you’re getting closer though.