Learn the science behind:

How Malted Grains Are Made – The Magic of Malting

Brewers need malt to make delicious beer. Bakers use malt or diastatic powder to optimize their daily bread. Malt is a grain that’s been allowed to sprout, but only just a little. This ensures that all valuable sugars and proteins in the grain become available for the brewers and bread bakers. It’s a surprisingly complex, but fascinating topic.

This is a guest post by Niels Langenaeken who researches the role of cereals in beer brewing at the KU Leuven where he’s part of the Laboratory of Food Chemistry & Biochemistry. He also coordinates the postgraduate program Malting and Brewing Sciences.

Let the plant grow (just a little bit)

Germinating grains is something that farmers are good at in their fields. It’s the starting point of a new plant. When malting grains, you start by steeping and also germinating them. The only difference is that no soil is used in this process.

You want to provide your grain – barley, wheat or mostly any intact grain – with all the conditions so that it can start growing a plant. This means that you need at least water, some moderate heat and time.

During germinatinon, grains use their inner starch reservoir as an energy source. In order to use that energy source, the plant makes enzymes and releases them. They convert the starch so a plant can use that energy.

However, to make malt, you don’t want to fully sprout the grains. You only want enough of these enzymes. So, the process is stopped prematurely by dehydrating the kernels so the plant growth is limited.

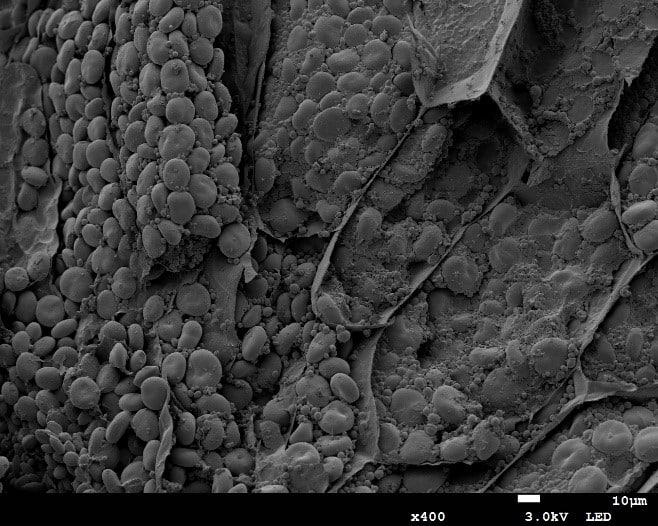

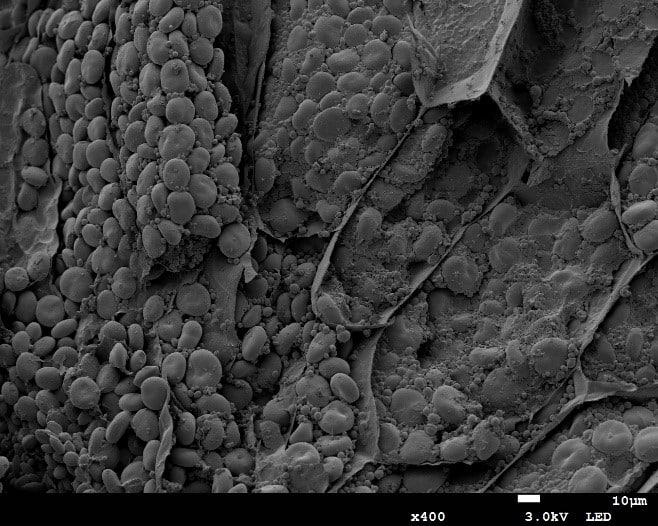

Grain architecture

Before we can explain what happens during this wonderful process, it is necessary to have a decent look inside a kernel. In the figure above, a barley kernel was cut open and put under a Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM). On the right image, the spheres are starch granules (the energy source) and they are densely packed in an orderly fashion inside the kernel. Between all granules, protein holds everything into place. The starch and protein are packed in so-called endosperm cells that cover everything with a thick cell wall. These cell walls consist of fibers (non-digestible carbohydrates) to which various health benefits are ascribed.

Surrounding all these endosperm cells is a kernel’s outer layer (only visible in the left photo). This is where a grain kernel keeps its goodies. There, in the aleurone layer, all enzymes are located, together with plenty of minerals.

Release the enzymes, break the walls

The first start in an industrial malting process is the rehydration of the grains. During this steeping phase, whole grain kernels take a dive in water at room temperature (15-20 °C). They will take up water until a moisture content of 40-45% is reached. This takes mostly 1-2 days, while wet and dry phases are alternated.

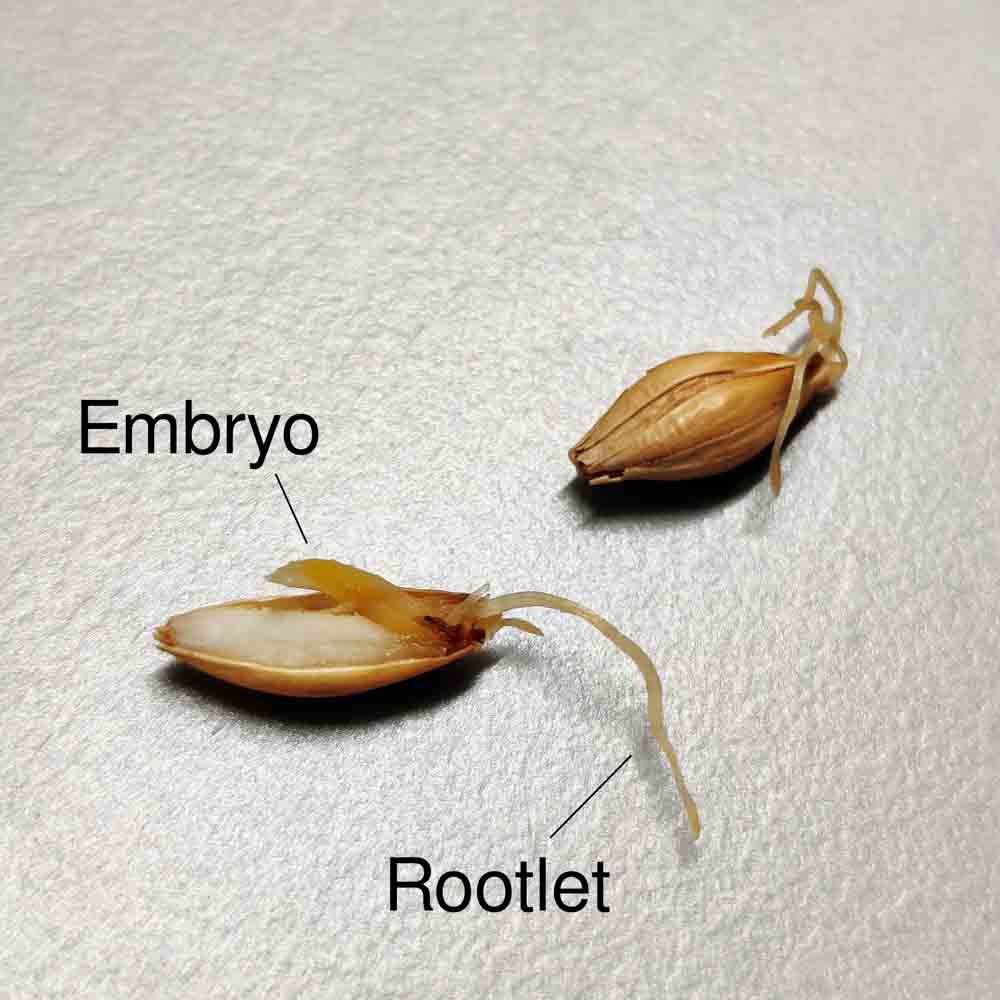

After steeping, the kernels are left to germinate on the so-called germination floor, for 2 to 7 days, depending on the type. The kernels will germinate, forming rootlets and a little sprout. It’s the start of a new plant. Maltsters look at the length of the ‘sprout’ (embryo) to follow the process. Ideally, the sprout has a length of 75% of the length of the entire kernel.

When you zoom in on the kernel, you’d notice that, apart from the visible growth of the sprout, a lot of processes take place during steeping and germination:

1. Release of enzymes

Once the kernel takes up water, a whole machinery is activated that liberates enzymes and produces new ones. These enzymes are proteins that act as catalysts in biochemical reactions. The enzymes are mostly located in the outer layers of the kernel.

2. Degradation of cell walls

The first enzymes that are produced in the kernel are needed to breakdown the cell walls that compartmentalize the starch reservoir. While water is penetrating the kernel, the enzymes follow its path and cell walls are degraded accordingly. This makes the starch granules and the protein accessible for other enzymes. The cell walls of the aleurone layer are also degraded and some of the minerals are now accessible.

3. Breakdown of starch and protein

Enzymes that can degrade starch and protein are produced as well. On the field, these enzymes would convert the full inside of the kernel to useful building blocks for the plant. During germination in a factory, starch and proteins are only degraded to a limited extent. A slight degradation of starch might result in some sugars (sweetness!), while the degradation of protein will result in the production of amino acids (flavor!, think Maillard). Just how much of these proteins and starch are degraded is tightly controlled by the maltsters since this has a big impact on the final quality of the malt.

Apply heat, produce flavor

If you would like to use these germinated kernels for brewing, baking or distilling purposes, an additional step is required to stop the germination process. This process is called kilning. The kernels are dried by blowing warm air through the kiln bed. A strict protocol is used for every type of malt, but for standard pilsner malt, kilning starts with a gentle heat of about 40-50 °C, which is continuously increased until a maximum of 80-90 °C. The full kilning process can take up to a day. By applying heat to the kernels, the moisture content is reduced again, which stops all biochemical processes including germination. Care is taken not to inactivate the enzymes though. You still need the enzymes when using the malt in its final application.

Moreover, and equally important, flavor is formed during drying. The heat initiates the Maillard reaction. Again, producers tightly control the temperatures to get the right amount of flavor and color formation. If you want more flavor, then caramel malts are your thing. For caramel malts, the germination process is tuned to make a lot of sugars and amino acids. The kernels are then exposed to high temperatures that will get the Maillard reaction going. The result is a glassy caramel-like grain kernel, packed with flavor.

Using malts

Once the malts have been dried, they can be stored for quite some time, until they are used to make beer, bread, or other products. Every application has slightly different needs with regard to flavor, color and activity of the enzymes.

Application in brewing

Kilned malt has a moisture content below 5% and can be stored at room temperature. Brewers mill malt and add it to the mashing water. There the enzymes that were formed during malting get to work. They convert the starch to fermentable sugars. These fermentable sugars are converted to alcohol, CO2 and flavor by the yeast, making beer.

The type of malt has a strong influence on the final beer quality. Brewers make a malt blend according to their recipe. The majority of the blend consists of pilsner malt, as this malt contains the most enzymes. The darker the color of the malt, the fewer enzymes it contains. Caramel malts add that specific caramel, toffee, biscuit flavor to beer. Roasted malts on the other hand tend to add coffee, cacao, dried fruit, or bread crust flavor. To make a dark brown beer, it suffices to include about 5% of roasted malt to obtain the right color!

Application in bread

Sometimes, a recipe calls for the addition of diastatic malt powder. ‘Diastatic means’ nothing more, or nothing less than ‘containing active enzymes’. A little bit of malt powder will increase the enzyme levels in your bread, which is beneficial, but only up to a point.

This article only just scratches the surface of all the fascinating processes that occur during malting. There is ample more (scientific) literature available to learn just exactly what happens. Still, researchers still don’t fully understand everything, thus research continues to take place.

References

All colleagues at the Lab of Food Chemistry and Biochemistry – KU Leuven

Kunze, W., Technology Brewing and Malting. VLB: Berlin, 2016.

This is a guest post by Niels Langenaeken who researches the role of cereals in beer brewing at the KU Leuven where he’s part of the Laboratory of Food Chemistry & Biochemistry. He also coordinates the postgraduate program Malting and Brewing Sciences.

What's your challenge?

Struggling with your food product or production process? Not sure where to start and what to do? Or are you struggling to find and maintain the right expertise and knowledge in your food business?

That's where I might be able to help. Fill out a quick form to request a 30 minute discovery call so we can discuss your challenges. By the end, you'll know if, and how I might be able to help.